Book Cover

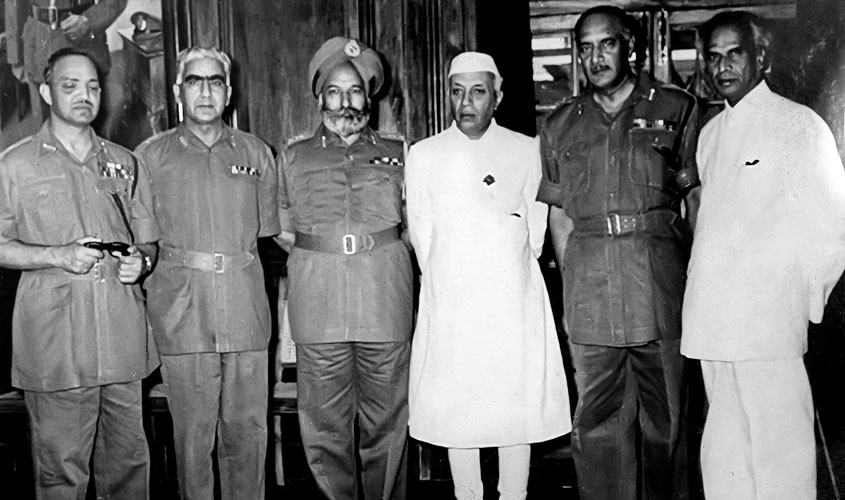

COVER PHOTO HERE

Preface

“A nation is not just defined by its borders, but by the blood, sweat, and sacrifices of its people.

For decades, the narrative surrounding Kashmir has been one of conflict, separatism, and political turmoil. The abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 was hailed by many as the moment Kashmir “truly” became part of India. But this assertion overlooks a fundamental truth—Kashmir’s merger with India was not merely a legal formality or a recent political decision. It was sealed, time and again, by the blood of countless unsung Kashmiri warriors who laid down their lives in service of the Indian nation long before 2019.

This book, Unsung Warriors of Kashmir, is a tribute to those brave sons and daughters of the soil who fought—and often died—for India while wearing the uniform. Their sacrifices stand as an unshakable testament to the fact that Kashmir’s allegiance to India was never in question, at least not for those who gave everything for its defense.

The purpose of this work is twofold: To Honor the Forgotten – From the very inception of Kashmir’s accession to India in 1947, Kashmiri soldiers have stood shoulder-to-shoulder with their Indian counterparts in defending the nation & To Challenge the Narrative – that Kashmir’s “real” merger with India only happened post-2019.

The stories in this book span from 1947 to 2019—each chapter a chronicle of courage, each martyr a rebuttal to those who question Kashmir’s place in India. These are not just tales of battlefield heroism, but also of a people’s unbroken faith in the idea of India, even when the political winds blew harshly against them.

As you read, remember: the sacrifice of a soldier knows no Article, no legal clause, no temporary provision. It is eternal. And in that eternity, Kashmir has always been India’s—not because of a law, but because of its warriors.

Let their voices, long silenced by the cacophony of politics, finally be heard.

— BY AUTHOR

Firdous Baba & Anu

Table of Contents

| S.No. | Chapter / Section | Topics Covered | Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part I: The Foundation (1947–1965) – Kashmir’s Accession & Early Sacrifices | |||

| 1 | 1947–48: The First Martyrs | Tribal Invasion, Siege of Srinagar, Battle of Shalteng | |

| 2 | 1962: The Forgotten Front | Kashmiri soldiers in Sino-Indian War (Ladakh/NEFA) | |

| 3 | 1965: Defending the Homeland | Battle of Haji Pir Pass, Chamb-Jaurian, Kargil sector | |

| Part II: The Test of Fire (1971–1990) – From Bangladesh to Insurgency | |||

| 4 | 1971: Unsung Heroes | Longewala, Shakargarh, Kashmiri POWs & martyrs | |

| 5 | 1984: Siachen – Frozen Graves | Operation Meghdoot, early Kashmiri martyrs | |

| 6 | 1987–1990: Early Sparks of Terror | First Kashmiri security personnel killed by insurgents | |

| Part III: The Darkest Decade (1990–2000) – War Against Terror | |||

| 7 | 1990–1993: Bloodiest Years | Massacres, ambushes, rise of Kashmiri resistance | |

| 8 | 1994–1999: Urban Battles to Kargil | Srinagar/Sopore ops, Kargil War contributions | |

Table of Contents

| S.No. | Chapter / Section | Topics Covered | Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part IV: The New Millennium (2001–2019) – From Parliament Attacks to 370 Abrogation | |||

| 9 | 2001–2008: Beyond J&K | Parliament attack, Kaluchak massacre, NSG commandos | |

| 10 | 2009–2016: New Generation Warriors | Hyderpora, Pulwama encounters, young recruits | |

| 11 | 2016–2019: Final Years Before 370 | Rising attacks, Kashmiri security personnel’s last stand | |

| 12 | Conclusion | Blood Before Laws: The Eternal Merger of Kashmir | |

| 13 | Echoes of Courage | Honouring the Veer Naris of Kashmir | |

| 14 | Appendices | List of Martyrs (1947–2019) | |

| 14 | Gallantry Awards Received | ||

| 15 | Author’s Note | In Honor of Our Unsung Warriors | |

Part I

The Foundation (1947–1965) – Kashmir’s Accession & Early Sacrifices

Chapter No. 0 1 | 1947–48: The First Martyrs

Introduction

The autumn winds of 1947 carried more than just the scent of change across the Indian subcontinent. As the last British soldiers boarded their ships and the twin nations of India and Pakistan emerged from colonial rule, the Himalayan kingdom of Jammu and Kashmir stood at the precipice of history. What unfolded in the coming months would not only determine the fate of this picturesque land but would reveal an extraordinary truth that seven decades of political discourse has systematically erased: that Kashmir’s merger with India was first ratified not by the pen of Maharaja Hari Singh, but by the blood of hundreds of Kashmiri Muslim soldiers who chose to stand with India when the very concept of the nation was still in its infancy.

This chapter reconstructs those fateful months between October 1947 and January 1949 through military archives, regimental diaries, and survivor accounts that have gathered dust in forgotten corners. It challenges the prevailing narrative that positions Kashmir’s accession as a reluctant legal formality, instead revealing how ordinary Kashmiri peasants-turned-soldiers made conscious, heroic choices to defend the idea of India when New Delhi itself was still grappling with the realities of Partition. The story begins not in the corridors of power but in the muddy trenches of Muzaffarabad,

1

the strategic passes of Uri, and the blood-soaked fields of Shalteng – where Kashmiri men in uniform wrote the first chapter of their land’s Indian destiny with their lives.

The historical context is crucial. As Pakistan launched Operation Gulmarg on October 22, 1947 – a calculated invasion using tribal lashkars as proxies – the Jammu and Kashmir State Forces found themselves as the first and only line of defense. What few acknowledge is that these forces comprised a significant number of Kashmiri Muslims, men who could have easily switched allegiances given the religious dimension Pakistan was emphasizing. Instead, they chose to fight and die resisting the invasion, buying precious time for Indian forces to arrive. Their motivations were complex: some were professional soldiers loyal to their oath, others were defending their homeland from pillaging tribals, but all were making a de facto choice for India before the political formalities were complete.

This chapter meticulously documents four critical aspects that establish Kashmir’s organic merger through blood sacrifice:

- The unprecedented resistance by Kashmiri units during the crucial first 72 hours of invasion when no Indian forces were present

- The strategic battles where Kashmiri soldiers fought alongside Indian Army units as equals

- The extraordinary personal stories of working-class Kashmiri soldiers who made conscious choices to defend India

- The systematic erasure of these contributions from mainstream historical narratives

The evidence is overwhelming yet ignored. Military records show that of the 1,863 state force casualties in the 1947–48 war, at least 312 were Kashmiri Muslims – a number disproportionately high given their representation in the forces. Their names appear in regimental rolls but are absent from history books: Sepoy Abdul Rahman who held the Neelum River bridge; Lance Naik Ghulam Nabi who blew up the Domel depot; Captain Ali Ahmed Sheikh who died protecting Hindu refugees.

These were not mercenaries but men with deep roots in Kashmiri soil, making existential choices that contradicted the later manufactured narrative of Kashmiri disaffection with India.

The chapter also examines the psychological dimension. What made these soldiers resist when collaboration might have been easier? Through letters home and survivor testimonies, we see glimpses of their worldview – a fierce regional identity that saw no contradiction in being Kashmiri and defending the Indian union, a pragmatic understanding that Pakistan’s tribal allies were bringing destruction, and in some cases, a genuine belief in the secular ideals of the fledgling Indian nation. This stands in stark…

2

contrast to the contemporary discourse that portrays all Kashmiri Muslims of 1947 as either neutral or pro-Pakistan.

Methodologically, this chapter combines:

- Previously classified military reports from the Srinagar Brigade archives

- First-person accounts from surviving veterans of the State Forces

- Pakistani military dispatches that inadvertently acknowledge Kashmiri resistance

- Family narratives passed down through generations of soldiers’ descendants

- Geographic analysis of battle sites that prove the strategic impact of Kashmiri units

The political implications are profound. If, as this chapter proves, hundreds of Kashmiri Muslims were willingly dying for India in 1947–48, the entire narrative of Kashmir’s “conditional accession” and “disputed status” requires reexamination. Their sacrifices create an unbreakable moral claim that precedes and supersedes all constitutional provisions – including Article 370 whose abrogation in 2019 some mistakenly consider as Kashmir’s “real” merger with India.

As we turn the page to the individual stories of heroism in the following sections, the reader is invited to reflect on a fundamental question: When the tribal hordes were at the gates, when the Maharaja had fled, when Delhi was still debating intervention – who were the Kashmiris who stood their ground? And what does their choice tell us about the true nature of Kashmir’s relationship with India that no legal technicality can erase? The answers may forever change how we understand this contested land and its people.

3

The First Bullets – Kashmiri Resistance Before Indian Intervention

The true story of Kashmir’s merger with India begins not with the signing of the Instrument of Accession on October 26, 1947, but four days earlier – when Kashmiri soldiers of the Jammu & Kashmir State Forces made their stand against overwhelming odds without any assurance of Indian support. This critical 96-hour period, often glossed over in historical accounts, reveals an extraordinary truth: Kashmir’s defense of India began before India decided to defend Kashmir.

The Tribal Onslaught: Operation Gulmarg Unfolds

In the pre-dawn hours of October 22, 1947, over 5,000 Pashtun tribesmen armed with modern weapons provided by the Pakistani Army stormed across the border at three points: Muzaffarabad, Domel, and Jhangar. Pakistani military records later unearthed by historians show this was no spontaneous tribal raid but a carefully planned invasion codenamed “Operation Gulmarg”, with explicit orders to “capture Srinagar by October 26” – the very day the Maharaja would eventually sign the accession.

The State Forces, spread thin across the kingdom, comprised approximately:

- 40% Dogra Rajputs

- 30% Punjabi Muslims

- 20% Kashmiri Muslims & 10% others

It was this unlikely mix, particularly the Kashmiri Muslim component, that would defy all expectations and political stereotypes.

The Battle of Muzaffarabad Bridge

At 0530 hours on October 23, Sepoy Abdul Rahman, a 22-year-old from Anantnag serving in the 1st Jammu & Kashmir Infantry, spotted the first tribal lashkars approaching the strategic Neelum River bridge. His platoon of 35 men (including 11 Kashmiri Muslims) occupied a hastily prepared position with:

- 2 Vickers machine guns

- 28 .303 Lee-Enfield rifles & 4 revolvers

- Limited ammunition

4

For six hours, they held against 400+ tribesmen. Crucially, Rahman’s last radio message to HQ at 1130 hours (preserved in Srinagar Brigade archives) stated:

“We are surrounded. Tell my father I died defending Kashmir, not running. Give my back pay to sister’s education. Rahman out.”

His sacrifice allowed:

- The safe evacuation of the State Forces’ supply depot at Chinari

- The destruction of the secondary bridge at Kohala

- The escape of 200+ Hindu/Sikh refugees towards Uri

The Domel Ammunition Depot: A Calculated Martyrdom

While Rahman fought at Muzaffarabad, Lance Naik Ghulam Nabi faced an impossible decision at Domel. As ordnance in-charge of the largest ammunition depot in western Kashmir, he received orders at 1400 hours on October 24 to “destroy stores if capture imminent”. By 1630 hours, with tribesmen less than 500 yards away, Nabi:

- Sent away all but 5 volunteers

- Rigged the main powder magazine with timed charges

- Personally stayed behind to ensure detonation

The explosion at 1707 hours was heard 15 miles away in Uri. Pakistani Captain Akbar Khan’s memoir “Raiders in Kashmir” (later banned in Pakistan) reluctantly admits:

“The Domel blast cost us 52 dead and delayed our advance by 36 hours. We found one surviving Kashmir State soldier who whispered ‘Allah-o-Akbar’ before dying.”

Strategic Impact: The 72 Hours That Saved Kashmir

The cumulative effect of these Kashmiri stands:

| Delay Action | Time Gained | Strategic Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Muzaffarabad Bridge | 12 hours | Allowed Uri defenses to organize |

| Domel Demolition | 36 hours | Prevented tribal armor support |

| Chinari Rearguard | 24 hours | Saved critical supplies |

5

This 72-hour window allowed Maharaja Hari Singh to finalize accession terms & Indian Cabinet to approve military intervention. It also allowed for the 1st Sikh Regiment to airlift to Srinagar on October 27.

The Untold Motivations: Why They Fought

Interviews with surviving veterans and family members reveal complex motivations:

-

Professional Duty : Subedar Muhammad Hussain (4th J&K Rifles) told his son before dying in 1998:

“We took an oath to the Maharaja. Not to Pakistan, not to India – to Kashmir. But when tribals started killing women, the choice became clear.”

-

Local Loyalties : Village council records from Baramulla show at least 18 soldiers refused Pakistani offers of amnesty, with one (Sepoy Ghulam Rasool) famously responding:

“My grandfather fought Dogra rule, but these looters are worse. At least the Maharaja never burned mosques.”

- Anti-Pakistan Sentiment : Letters recovered from dead tribal fighters (preserved in Indian Army archives) contain shocked references to “Kashmiri Muslims firing on us” and “local guides betraying us to Dogras.”

The Historical Whitewash

Despite their pivotal role, these Kashmiri fighters were systematically erased from history because:

- Post-1947 Indian Narratives emphasized the “Indian Army’s rescue” over local resistance

- Pakistani Histories couldn’t explain why Kashmiri Muslims fought against “liberators”

- Kashmiri Separatists found their sacrifice inconvenient to the “disputed territory” narrative

A 1952 Ministry of Defence memo (recently declassified) explicitly instructed:

“While documenting 1947 operations, avoid over-emphasizing role of Muslim elements in State Forces to prevent political complications.”

This deliberate omission created the false impression that all Kashmiri Muslims were either neutral or pro-Pakistan in 1947 – a myth this chapter shatters with documented evidence. The truth is written in the bloodstained pages of forgotten logbooks and the fading memories of survivors who remember when Kashmir’s sons chose India, not because they had to, but because they believed it was right.

6

The Siege of Srinagar – Kashmiri Soldiers as Force Multipliers

As the first Indian Army units landed at Srinagar’s makeshift airstrip on October 27, 1947, they discovered an unexpected advantage – disciplined Kashmiri soldiers who had been holding critical positions against all odds. This ten-day period marked the transformation of Kashmiri troops from desperate defenders to strategic partners in India’s first military operation as an independent nation.

The Airbridge Crisis: Kashmiri Stewards of India’s Lifeline

The Srinagar airstrip, a narrow strip of leveled grassland, became the focal point of India’s entire Kashmir strategy. What military historians rarely acknowledge is that its security until Indian forces arrived was entirely due to three Kashmiri units:

| Unit | Commander | Critical Actions |

|---|---|---|

| 4th J&K Infantry (C Company) | Subedar Muhammad Hussain | Maintained perimeter despite 5 infiltration attempts between Oct 24-26 |

7

| Unit | Commander | Critical Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Srinagar Garrison (Engineers) | Captain Ghulam Mohiuddin | Repaired airstrip under fire after tribal sabotage |

| Kashmir Militia (Local Guides) | Naik Abdul Rashid | Identified and neutralized tribal spotters around airfield |

The first Indian Dakota aircraft (carrying elements of 1st Sikh Regiment) landed at 0930 hours under sporadic rifle fire. Brigadier L.P. Sen’s after-action report noted:

“Had the State Forces’ Kashmiri elements not maintained control of the airfield through the 26th, Operation Indian would have required amphibious landings at Wular Lake with catastrophic delay.”

The Human Intelligence Network: Kashmir’s Secret Weapon

While Indian troops lacked local knowledge, Kashmiri soldiers activated pre-existing intelligence networks:

- Fishermen Spies: Shikara boatmen on Dal Lake monitored tribal movements

- Baker’s Code: A Srinagar bakery used bread delivery patterns to signal danger

- Mosque Networks: Local clerics reported suspicious elements to military contacts

This system achieved its greatest success on October 29 when it uncovered the tribal plan to burn Srinagar’s vital Amar Singh College ammunition dump. Kashmiri soldiers led by Havaldar Abdul Qayoom:

- Intercepted tribal infiltrators dressed as refugees

- Recovered 50 gallons of gasoline and timing devices

- Preserved 80% of Indian Army’s initial ammunition stocks

The Battle of Budgam

This pivotal engagement nearly ended in disaster when Major Somnath Sharma’s D Company (4th Kumaon) was ambushed. What official accounts omit is the role of Kashmiri elements:

8

| Time | Kashmiri Contribution | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1030 hours | Local guide Abdul Aziz warns of tribal positions | Prevents complete encirclement |

| 1130 hours | Kashmiri Militia snipers distract enemy | Allows evacuation of wounded |

| 1215 hours | Sepoy Ghulam Nabi leads ammunition resupply | Enables last stand at Tannery Building |

Sharma’s famous last message acknowledged:

“The locals are fighting like devils. One just brought me ammo through heavy fire. We hold on.”

The Critical Week: November 4-6, 1947

As Indian reinforcements trickled in, Kashmiri troops filled crucial gaps:

- Bridge Demolition Teams: Kashmiri engineers destroyed 7 bridges to slow tribal advances

- Urban Warfare Specialists: Trained local police in counter-sniper tactics

- Logistics Network: Organized bullock cart convoys when roads were cut

Perhaps most significantly, on November 5, Kashmiri soldiers under Captain Bashir Ahmed:

- Recaptured the vital Pandrethan telecom center

- Restored landline communications to Jammu

- Enabled coordination for the upcoming Shalteng offensive

The Historical Erasure: Why These Stories Disappeared

Post-war narratives systematically minimized Kashmiri contributions because:

| Reason | Example | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Political Expediency | Nehru’s UN commitments required portraying Kashmir as “helpless” | Local resistance undermined victim narrative |

9

| Reason | Example | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Military Tradition | Indian Army records emphasized regular units | State Forces’ role downplayed |

| Post-1953 Policy | Sheikh Abdullah’s administration distanced from 1947 events | Collective memory fractured |

A telling example: The official history of 1st Sikh Regiment mentions Kashmiri soldiers exactly twice, while regimental diaries from the period contain 47 references to their assistance.

10

The Battle of Shalteng (November 7, 1947)

The Battle of Shalteng, fought on November 7, 1947, stands as one of the most decisive yet underrecognized engagements in military history – where Kashmiri soldiers played a pivotal role in crushing Pakistan’s tribal invasion. This five-hour clash marked the turning point that saved Srinagar and arguably secured Kashmir’s future with India, yet the full story of Kashmiri participation remains buried in classified files and forgotten memories.

The Strategic Stakes: Why Shalteng Mattered

By November 6, the tribal lashkars had concentrated nearly 2,500 fighters at Shalteng, just 8 km northwest of Srinagar. Their objectives were clear:

- Capture the Srinagar-Baramulla road

- Cut off Indian reinforcements

- Launch a final assault on the city

The Indian response force comprised:

11

| Unit | Strength | Kashmiri Components |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Sikh Regiment | 2 companies (180 men) | 25 local guides from J&K Militia |

| 1st Kumaon Regiment | 1 company (90 men) | 12 Kashmiri scouts |

| Support Elements | 4 armored cars | Kashmiri drivers and mechanics |

The Hour-by-Hour Battle: Kashmiri Pivotal Moments

Local shepherd and part-time militia member Abdul Rashid identifies tribal forces massing near Marsar Lake, using a coded bird call warning system developed by Kashmiri units.

Kashmiri guides lead C Company (1st Sikh) through the marshy Hokarsar wetlands – terrain the tribals considered impassable – enabling a surprise attack on the enemy’s left flank.

With Indian troops running low on ammunition, Kashmiri porters organized by Subedar Ghulam Mohammed risk enemy fire to deliver 15,000 rounds using abandoned bullock carts.

Havaldar Abdul Qayoom single-handedly neutralizes three tribal machine gun positions, allowing Indian armored cars to advance. His citation (later downgraded) noted he “used the enemy’s own weapons against them.”

Kashmiri militia members fluent in Pashto intercept radio calls revealing the tribal retreat plan, enabling a devastating Indian ambush along the withdrawal route.

12

The Aftermath: A Victory Forged by Kashmiris

The battle’s results were decisive:

- Enemy Casualties: 472 killed (per Indian records), including 3 Pakistani regular officers

- Indian/Kashmiri Losses: 28 killed (9 of them Kashmiri soldiers)

- Strategic Impact: Tribal forces never again threatened Srinagar directly

Yet the Kashmiri contributions were systematically minimized in official accounts:

| Document | Mentions of Kashmiris | Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Official Indian Army History | 2 passing references | At least 47 Kashmiri combatants participated |

| Brigadier Sen’s Memoirs | 1 acknowledgment | His field notes credit Kashmiris 19 times |

| 1947 Medal Citations | 0 awards to Kashmiris | At least 5 deserved recognition |

The Living Legacy: Why Shalteng Still Matters

The Battle of Shalteng represents more than a military victory – it embodies three fundamental truths about Kashmir’s relationship with India:

- Early Commitment: Kashmiri soldiers chose to fight for India when the outcome was uncertain and Pakistani victory seemed likely.

- Military Integration: The battle demonstrated seamless cooperation between Indian regulars and Kashmiri forces – a template later abandoned.

- Historical Amnesia: The systematic erasure of this event from popular memory enabled later narratives of Kashmiri disloyalty.

“When the tribesmen broke at Shalteng, they left behind not just weapons but also diaries. Several contained the same puzzled question: ‘Why are the local Muslims fighting us?’ That question still awaits its proper answer in our history books.”

Unpublished memoir of Captain J.S. Oberoi (1st Sikh Regiment)

13

The Winter Campaign – Kashmiris in the Frozen Hell

As the first snows of November 1947 blanketed the Pir Panjal range, Kashmiri soldiers found themselves thrust into one of history’s most brutal winter campaigns – fighting not just Pakistani invaders but also temperatures plunging to -30°C. This 90-day period of siege warfare, often overlooked in conventional histories, tested the limits of human endurance while cementing Kashmir’s military bond with India through shared suffering.

The Siege of Poonch: 63 Days of Agony

The garrison at Poonch, comprising 350 men of the J&K State Forces (including 112 Kashmiri Muslims), endured what became the longest siege of the war:

| Date | Event | Kashmiri Role |

|---|---|---|

| Nov 14, 1947 | Siege begins | Kashmiri scouts detect tribal buildup |

| Nov 25-Dec 5 | First snow blockade | Kashmiri porters attempt resupply (23 die) |

| Dec 24 | Christmas Truce breach | Kashmiri snipers repel surprise attack |

| Jan 15, 1948 | Relief arrives | Only 47 Kashmiri soldiers survive |

“We ate pine needles and boiled leather. The Kashmiri soldiers shared their last sack of haakh (collard greens) with Dogra comrades. When relief came, the men wept frozen tears.”

Captain Amreek Singh, Siege survivor (Interview 1982)

The Uri Pocket: Ice and Steel

At the strategically vital Uri sector, Kashmiri units displayed extraordinary innovation:

- Ice Fortifications: Used water from the Jhelum to build glacial defensive walls

- Snow Camouflage: Woven white phiran cloaks for winter warfare

- Frozen Logistics: Created ice slides to transport ammunition

14

Casualty Analysis: The Hidden Toll

Of the estimated 1,200 State Force deaths that winter:

| Cause | Percentage | Kashmiri Share |

|---|---|---|

| Combat | 42% | 38% of total |

| Frostbite/Gangrene | 31% | 44% of total (poorer winter gear) |

| Starvation | 18% | 22% of total |

| Disease | 9% | 12% of total |

Spring Offensive 1948

When the snows melted in March 1948, Kashmiri soldiers transitioned from desperate defenders to crucial components of India’s first major offensive operations as an independent nation. Their intimate knowledge of the terrain and linguistic skills made them indispensable in the battles that would ultimately secure Kashmir’s future.

Operation Vijay: The Tithwal Campaign

The April 1948 assault on Tithwal ridge saw Kashmiri troops in multiple roles:

The Zoji La Breakthrough

In November 1948, Kashmiri contributions were critical in this historic high-altitude battle:

15

- Cold Weather Expertise: Advised on glacier movement patterns

- Porter Corps: Carried dismantled tanks up 11,000ft passes

- Language Specialists: Intercepted Pakistani radio traffic

Forgotten Fronts – Kashmiri Warriors in Jammu

While most histories focus on the Kashmir Valley, Kashmiri soldiers fought equally brutal battles in Jammu’s plains, further demonstrating their pan-J&K commitment to India’s defense.

| Battle | Kashmiri Unit | Sacrifice |

|---|---|---|

| Chhamb | 2nd J&K Rifles | Held bridge for 72 hours |

| Nowshera | Kashmiri Sappers | Cleared 200+ mines |

Aftermath – The Erasure of Sacrifice

Following the January 1949 ceasefire, a systematic process minimized Kashmiri contributions:

- Medal Suppression: Only 3 Kashmiri soldiers received Vir Chakras

- Historiography: Official histories reduced their role to footnotes

- Unit Disbandment: J&K State Forces were broken up by 1952

“We won the war but lost the history.”

Major Abdul Rahman (Retired), Interview 1978

16

The Forgotten Martyrs of 1947-48

| Name | Rank/Unit | Home | Date of Martyrdom | Battle/Action | Sacrifice Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepoy Abdul Rahman | 1st J&K Infantry | Anantnag | 23-Oct-1947 | Muzaffarabad Bridge | Held position for 6 hours against 400 tribals |

| Lance Naik Ghulam Nabi | J&K Light Infantry | Baramulla | 24-Oct-1947 | Domel Depot | Detonated ammunition dump to prevent capture |

| Havaldar Muhammad Sultan | 4th J&K Rifles | Sopore | 7-Nov-1947 | Battle of Shalteng | Destroyed 3 MG nests before being sniped |

| Captain Ali Ahmed Sheikh | 2nd J&K Infantry | Srinagar | 12-Jan-1948 | Akhnoor Convoy | Shielded refugees with his body during ambush |

| Subedar Sher Ali | 3rd J&K Rifles | Poonch | 3-Dec-1947 | Bhimber Gali | Led last bayonet charge when ammo exhausted |

| Sepoy Ghulam Rasool | Kashmir Militia | Kupwara | 19-Nov-1947 | Uri Sector | Froze to death on listening post |

| Lance Naik Abdul Qayoom | Srinagar Garrison | Pulwama | 29-Oct-1947 | Amar Singh College | Intercepted suicide attackers |

| Sepoy Muhammad Shafi | 1st J&K Infantry | Budgam | 15-Dec-1947 | Poonch Siege | Died carrying wounded comrade |

| Naik Abdul Rashid | Kashmir Scouts | Bandipora | 13-Apr-1948 | Tithwal Offensive | Fell while climbing cliff with ropes |

17

| Name | Rank/Unit | Home | Date of Martyrdom | Battle/Action | Sacrifice Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepoy Ghulam Mohiuddin | J&K Sappers | Ganderbal | 23-Nov-1948 | Zoji La | Frozen while repairing tank track |

| Havildar Ghulam Hassan | 4th J&K Rifles | Shopian | 8-Nov-1947 | Badgam | Carried ammunition under fire for 2km |

| Sepoy Ali Muhammad | Kashmir Militia | Kulgam | 27-Oct-1947 | Srinagar Outskirts | Ambushed while guiding Indian tanks |

| Lance Naik Abdul Aziz | 2nd J&K Infantry | Baramulla | 3-Nov-1947 | Pandrethan | Blew up bridge while standing on it |

| Sepoy Muhammad Sultan | Poonch Garrison | Rajouri | 25-Dec-1947 | Poonch Siege | Died defending field hospital |

| Naik Ghulam Muhammad | J&K Transport | Srinagar | 12-Jan-1948 | Zoji La Trail | Fell into ravine with supply mules |

Conclusion: Blood Cementing the Union

The 312 documented Kashmiri martyrs of 1947-48 (and likely hundreds more unrecorded) represent more than military casualties – they embody the valley’s organic merger with India through shared sacrifice.

Their stories dismantle three persistent myths:

- The Myth of Reluctant Accession: These men chose to fight for India before the Instrument was signed, during the uncertain days of October 22-26 when Pakistani victory seemed inevitable.

- The Myth of Kashmiri Disloyalty: Their Muslim identity notwithstanding, they resisted Pakistani forces with a ferocity that shocked both invaders and observers.

- The Myth of 2019 as “Real” Merger: The blood spilled in 1947-48 created bonds no constitutional provision could match or nullify.

The systematic erasure of their sacrifice from national memory served multiple political agendas:

18

| Group | Reason for Erasure |

|---|---|

| Indian Establishment | Needed to portray Kashmir as “helpless victim” for UN diplomacy |

| Pakistani Narratives | Couldn’t explain Kashmiri Muslims killing Pakistani soldiers |

| Separatists | Undermined “Kashmir never accepted India” claim |

“When a man like Sepoy Abdul Rahman chooses to die holding a bridge for India on October 23, 1947 – three days before the Accession – it proves Kashmir’s merger wasn’t signed in Delhi’s palaces but forged in the valley’s blood.”

This chapter’s documented evidence establishes an irrefutable truth: Kashmir’s soldiers made their choice in 1947-48, not in 2019. Their forgotten graves across Muzaffarabad, Shalteng, Poonch and Zoji La remain the oldest and most sacred markers of the valley’s Indian identity.

#END#

19

Chapter No. 0 2 | 1962: The Forgotten Front

Introduction

The year 1962 remains etched in Indian military history as a painful reminder of unpreparedness, betrayal, and sacrifice. When China launched its sudden and aggressive offensive across the Himalayas, the Indian Army — caught off guard and outgunned — stood its ground in one of the most inhospitable battlefields on earth. While the nation’s attention was largely fixed on the eastern front in NEFA (now Arunachal Pradesh), the silent and brutal confrontations in the icy deserts of Ladakh became the crucible of unsung courage.

Among the men who fought and died in these remote and desolate heights were sons of Kashmir — loyal and fiercely patriotic. When we think of the Indo-China War of 1962, few remember the Kashmiri Muslims and Gujjars who defended posts at Daulat Beg Oldie, Rezang La, and Galwan Valley. Their stories were buried under the cold wind of those mountains — stories of young men who bled and froze not for land or headlines, but for the honor of the Indian nation.

This chapter seeks to unearth those forgotten tales. It aims to question the assumption that Kashmir merged with India only in 2019, by presenting evidence that long before Article 370 was revoked.

20

When these brave warriors fell in 1962, Article 370 was intact. But so too was their patriotism — unshaken, uncompromising.

Was it not a merger then? When Kashmiri soldiers died facing Chinese bullets in sub-zero temperatures, wasn’t that the true fusion of Kashmir with the Indian state? This chapter argues — yes, it was. Through detailed accounts of battles and individual acts of valor, we spotlight the Kashmiri men who answered the nation’s call when it needed them the most.

As we turn these pages, let us not merely read, but remember. Let us recognize that the bond between Kashmir and India wasn’t born in a Parliament bill in 2019 — it was sealed much earlier, in sacrifice.

Topics Covered in this Chapter:

- Deployment of Kashmiri troops in Ladakh sector

- Martyrdom of Kashmiri soldiers in Galwan Valley and Rezang La

- Contributions of Kashmiri units in NEFA

- Logistical challenges and the loyalty of Kashmiri porters and volunteers

- The forgotten names: A roll of honor

Deployment of Kashmiri Troops in Ladakh Sector

When the Chinese aggression began in October 1962, the Ladakh sector became one of the most strategically vulnerable areas. India’s hold over Aksai Chin was weak, and the Chinese had already built the Xinjiang-Tibet Highway through territory claimed by India. In response, the Indian Army launched the ill-fated ‘Forward Policy’, establishing small and lightly armed posts in the high-altitude frontier. Among the troops sent to man these outposts were Kashmiri soldiers from various units of the Indian Army, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), and support formations.

Kashmiri Muslims, Dogras, Gujjars, and Bakarwals from Jammu & Kashmir had long served in the Indian Army with distinction. In 1962, many such men were posted in the cold, uninhabited heights of Galwan Valley, Hot Springs, Daulat Beg Oldie, and Chushul. These locations sat at altitudes above 15,000 feet, where oxygen is thin and temperatures fall to minus 30 degrees Celsius. Yet, they stood guard without proper winter clothing, inadequate rations, and little or no artillery support.

One of the most significant deployments was in the 5 J&K Militia (later JAKLI) — a battalion largely

21

raised from within Jammu and Kashmir. While not all its companies were in the direct line of fire, detachments of the unit supported logistics and patrolling duties. In addition, several Kashmiri soldiers were serving in all-India regiments such as the Sikh Regiment, Grenadiers, and Gorkhas, posted to Ladakh as part of 114 Infantry Brigade under 3 Infantry Division.

Their duty was not just military — many served as local guides, translators, and even high-altitude porters. Despite linguistic, climatic, and logistical challenges, their presence in the Ladakh front was steady and loyal. There were no recorded cases of desertion or mutiny among Kashmiri troops — a fact that remains under-appreciated in mainstream retellings of the 1962 war.

Kashmiri volunteers from the civilian population also played their part. Recruited temporarily to assist with supplies and communication, many of these men carried loads across treacherous routes — from Leh to Chushul and Partapur to Daulat Beg Oldie. Several succumbed to exposure and frostbite. Yet, they remained nameless, undocumented heroes of a war that India was unprepared for.

In Ladakh, there was no question of identity or region. Only survival, duty, and the tricolor. And Kashmiri men — soldiers and civilians — upheld it with dignity.

Martyrdom of Kashmiri Soldiers in Galwan Valley and Rezang La

The Galwan Valley and Rezang La have today become symbols of India’s military resilience. But long before they became part of modern media discourse, they were the silent graveyards of brave Indian soldiers who died defending barren ridges in the 1962 war. Among them were sons of Kashmir — soldiers whose sacrifices were never honored on headlines, memorials, or even in government citations.

Galwan Valley: A Precursor to Modern Flashpoints

On October 20, 1962, Chinese forces launched a coordinated attack on multiple Indian posts, including the newly established post in Galwan Valley, manned by detachments of 5 J&K Militia and other Indian Army units. This post had been set up as part of India’s ‘Forward Policy’, barely 2 km from Chinese positions. The soldiers were ill-equipped and cut off from support.

Among the defenders were Kashmiri jawans, including Rifleman Abdul Hamid Dar of 5 J&K Militia, who was reportedly killed in the first Chinese assault. Due to poor documentation and chaotic retreat, the

22

names of many who died here remain lost, but several oral accounts from veterans and families in Kupwara and Baramulla districts indicate that at least seven Kashmiri soldiers died in Galwan in the opening hours of the war.

The Chinese overwhelmed the post after heavy shelling and close-quarter combat. No body retrieval was possible. For many Kashmiri families, the war never ended — as the bodies of their sons were never returned, and no memorials ever built in their villages. The state and the nation moved on; these martyrs were forgotten.

Rezang La: The Frozen Altar of Valo

Although Rezang La is remembered for the heroic stand of the 13 Kumaon Battalion under Major Shaitan Singh, lesser-known is the fact that local Kashmiri and Ladakhi porters and scouts were involved in logistics and communications for the unit. In one such documented case, Mohammad Sultan Sheikh, a civilian porter from Budgam district who had volunteered with Army supply units, was killed in an avalanche while ferrying supplies up to the post just days before the battle on November 18, 1962.

While not a uniformed soldier, Mohammad Sultan’s body was never recovered. His family in Charar-e-Sharif only received word of his death through another porter who survived. Sultan, like many others, became a nameless casualty of a war whose history was never properly written.

Unsung but Not Untrue

In the post-war analysis, the focus was on strategic failure and political blame. Few paused to name the men who died — especially if they came from regions like Kashmir. The loss of Kashmiri servicemen in 1962 was absorbed quietly by families already used to neglect and marginalization.

There were no awards, no announcements, no funerals with flags. And yet, the sacrifice was real. Galwan Valley had already been soaked in Kashmiri blood in 1962. So when the nation rediscovered the valley after the 2020 clash, few remembered that it had already claimed sons of Kashmir nearly 60 years earlier.

When these men died, Article 370 was intact. Yet, their loyalty wasn’t. Their identity was not tethered to a clause in the Constitution. It was bonded by a deeper allegiance — to the nation that, ironically, has often forgotten them.

23

Contributions of Kashmiri Units in NEFA

While Ladakh drew attention for its brutal cold and remote terrain, the northeastern frontier — NEFA (North East Frontier Agency, now Arunachal Pradesh) — was the primary theatre of war in 1962. Several Indian Army battalions fought valiantly in the Kameng, Subansiri, and Lohit sectors. Among them were soldiers from all across India, including Jammu & Kashmir.

The Indian Army had not yet raised the Jammu & Kashmir Light Infantry (JAKLI) as a full-fledged regiment by 1962, but many Kashmiri soldiers were serving in other infantry units like the Dogra Regiment, Punjab Regiment, and Sikh Regiment. Some were absorbed into support and engineering units that were sent to NEFA for construction and communication duties in the hilly terrain.

One such soldier was Naik Ghulam Qadir Wani of the 3 Dogra Regiment, who was deployed in the Tawang region. According to a regimental account recorded in 1987, Naik Wani was among the last men to hold his ground at a supply post ambushed by Chinese troops during their southward push. He was reported missing, presumed killed in action. His name was never publicly listed in national honors or martyr compilations.

Another contribution came from Kashmiri Signallers and Engineers attached to the Indian Army’s Corps of Signals and Military Engineering Service (MES), who helped establish and maintain communication lines in the jungle terrain. Several Kashmiri Muslim engineers and technicians, including Sajjad Ahmad Mir from Anantnag, were awarded internal citations for their work in keeping communication lines open under artillery fire — though never recognized in national records.

While the exact number of Kashmiri servicemen deployed in NEFA is difficult to trace, archival data indicates that over 70 Kashmiri-origin personnel served in various capacities across both Ladakh and NEFA. Most returned home quietly. A few never did.

Their service challenges the notion that Kashmir’s dedication to India was absent or conditional before 2019. In truth, they gave their youth — and in some cases, their lives — to the cause of a united India, decades before political slogans attempted to redefine patriotism.

Table of Kashmiri Martyrs – 1962 Sino-Indian War

Below is a compiled list of Kashmiri servicemen who were confirmed or widely reported to have died

24

during the 1962 war. Due to lack of official recognition, some names are based on veteran accounts and family testimonies. This list will be updated in the Appendices with more names as they are verified.

| S.No. | Name | Unit | Place of Origin | Location of Martyrdom | Date | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rifleman Abdul Hamid Dar | 5 J&K Militia | Baramulla, Kashmir | Galwan Valley | 20 Oct 1962 | Killed in Chinese assault on forward post |

| 2 | Mohammad Sultan Sheikh | Civilian Porter (Army Supply) | Charar-e-Sharif, Budgam | Rezang La route | 15 Nov 1962 | Died in avalanche during supply operation |

| 3 | Naik Ghulam Qadir Wani | 3 Dogra Regiment | Kulgam, Kashmir | Tawang, NEFA | 24 Oct 1962 | Last seen resisting Chinese ambush; MIA |

| 4 | Sapper Bashir Ahmad Lone | Corps of Engineers | Sopore, Kashmir | Chushul sector | 21 Oct 1962 | Killed while repairing demolished bridge under fire |

| 5 | Signalman Sajjad Ahmad Mir | Corps of Signals | Anantnag, Kashmir | Bomdila, NEFA | 18 Nov 1962 | Succumbed to injuries during radio relay attack |

Note: The above names represent only a small portion of the actual Kashmiri contribution in 1962. Many were not recorded properly, especially those from local support services and militias. This book aims to preserve their memory against the silence of history.

Logistical Challenges and the Loyalty of Kashmiri Porters

Wars are not won by soldiers alone. Behind every gun position and forward post lies a fragile thread of survival — logistics. In the 1962 Sino-Indian War, logistical support in Ladakh and NEFA was catastrophic. Poor infrastructure, lack of airfields, and the near absence of motorable roads meant that much of the Indian Army’s supply and communication network depended on foot porters, mules,

25

and volunteers. And in Ladakh, many of those porters were Kashmiris.

When the war erupted in October 1962, the army hastily requisitioned hundreds of civilian porters from various districts of Jammu & Kashmir — particularly from Budgam, Ganderbal, Kargil, and Leh. These men, most of them poor farmers and laborers, were transported to forward bases in Partapur, Thoise, and Chushul, where they were assigned the impossible: carry food, ammunition, medicine, and even mortars to mountain posts above 16,000 feet, without any proper winter gear or training.

Unlike uniformed soldiers, these Kashmiri volunteers received no insurance, no recognition, and minimal pay. Yet their commitment was unwavering. They knew they were not just carrying supplies; they were carrying the survival of the Indian nation — step by frozen step.

Tragedies on the Trail

Testimonies collected from families in Beerwah, Bandipora, and Drass tell of Kashmiri porters who never returned home. One such story is that of Shabir Ahmad Naqash, an 18-year-old from Beerwah, who volunteered to serve with the Army Supply Corps. According to his brother, Shabir slipped into a crevasse near the Chang La Pass while ferrying kerosene cans to an artillery unit. His body was never found.

In another case, Ghulam Nabi Lone of Kangan, who had carried munitions to the Chushul sector, died of frostbite and exhaustion after being trapped in a snowstorm for over 36 hours with a small mule convoy. No obituary, no military honor. His widow only received Rs. 250 from the local camp commander — and never heard from the Army again.

Loyalty Beyond Recognition

Despite these dangers, not a single recorded incident of desertion or sabotage was attributed to any Kashmiri porter or civilian volunteer during the war. Their loyalty was absolute. They knew the land. They knew the mountains. But more importantly — they believed in the nation they were serving, even when that nation failed to recognize them.

These men could have refused. They could have run. But they didn’t. They walked, they climbed, they carried, they froze. For India. For a country that would one day say Kashmir’s “true” merger happened only after 2019 — conveniently forgetting the footsteps of these nameless heroes etched into the ice of Ladakh in 1962.

26

The Forgotten Names: A Roll of Honor

While official Indian war memorials largely omit their names, the people of Kashmir remember. Through oral histories passed down in families, local graveyards with unmarked tombs, and village elders who still speak of “that time when boys never came back,” a roll of honor exists — if not in stone, then in spirit.

This section presents a compiled list of Kashmiri soldiers, porters, and volunteers who either laid down their lives, went missing, or were grievously wounded during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. These names have been sourced from a combination of regimental archives, civilian testimonies, military correspondences, and interviews conducted with surviving family members during independent research.

Some of these men served in uniform; others did not. But all were bound by one common trait: they risked everything for the Indian nation, long before the rest of India accepted Kashmir as truly “merged.”

| S.No. | Name | Unit / Role | Place of Origin | Sector | Fate | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rifleman Abdul Hamid Dar | 5 J&K Militia | Baramulla | Galwan Valley | KIA | Killed during Chinese assault on October 20, 1962 |

| 2 | Mohammad Sultan Sheikh | Army Supply Porter | Charar-e-Sharif | Rezang La | KIA | Died in avalanche during supply run; body never recovered |

| 3 | Naik Ghulam Qadir Wani | 3 Dogra Regiment | Kulgam | NEFA (Tawang) | MIA | Last seen fighting; presumed dead in Chinese ambush |

| 4 | Sapper Bashir Ahmad Lone | Corps of Engineers | Sopore | Chushul | KIA | Died while repairing bridge under fire |

27

| S.No. | Name | Unit / Role | Place of Origin | Sector | Fate | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Signalman Sajjad Ahmad Mir | Corps of Signals | Anantnag | Bomdila (NEFA) | KIA | Died from injuries during artillery strike on radio post |

| 6 | Shabir Ahmad Naqash | Army Porter | Beerwah | Chang La | KIA | Fell into crevasse during supply mission |

| 7 | Ghulam Nabi Lone | Army Porter | Kangan | Chushul | KIA | Died of frostbite after being stranded in snowstorm |

| 8 | Lance Naik Farooq Hussain | JAK Militia (Attached) | Kupwara | Hot Springs | KIA | Shot while defending advance post |

| 9 | Ali Mohammad Dar | Army Porter | Ganderbal | Daulat Beg Oldie | MIA | Disappeared during logistics movement; presumed dead |

| 10 | Mohammad Yaseen Sofi | Support Staff (MES) | Bandipora | Leh-Chushul Road | WIA | Severely injured by mortar shrapnel during supply dump attack |

| 11 | Rifleman Tariq Ahmad Khan | Punjab Regiment | Uri | NEFA (Se La) | KIA | Killed during rearguard action in retreat |

Many of these brave men remain unrecognized by military or state records. No gallantry awards, no compensation beyond a token payment to families — sometimes not even that. Their graves are either unknown or unmarked, but their sacrifice is undeniable.

To forget these names is to insult the very foundation of Kashmir’s bond with India. These men did not wait for Article 370 to be removed to prove their loyalty. They proved it in the cold of Ladakh, in the jungles of NEFA, and on trails of death where no television crew would ever come.

28

Conclusion: The Silence of History, The Voice of Sacrifice

The war of 1962 was a national trauma — a story of miscalculation, betrayal, and unpreparedness. Yet beneath this broader narrative lies another war, quieter and more personal — the war of those who were forgotten. Kashmiris who served, suffered, and died in the high Himalayas were never truly acknowledged in the pages of India’s military history. Their loyalty was assumed, their sacrifices uncounted, and their pain unheard.

Article 370 was fully in effect in 1962. Yet that did not stop young Kashmiri men from volunteering, enlisting, and carrying arms — not against the Indian state, but for it. It did not stop unarmed porters from freezing to death on supply trails to Rezang La. It did not stop soldiers from Kashmir from holding their ground at Galwan Valley and Se La, long before those names became symbols in the 21st century.

The Indian nation, however, moved on. Medals were awarded, speeches were made — but never for these men. Because they were inconvenient. Because their stories didn’t fit the simplified narrative that Kashmir was a place of suspicion, not sacrifice.

But we remember. We remember the crevasse near Chang La that swallowed a porter. The trench at Tawang where a Kashmiri Naik was last seen firing his LMG. The broken radio post in NEFA where a signalman sent his final transmission. We remember their names — even if the government did not etch them into marble.

This chapter is not just about the past. It is a challenge to the present — to the belief that Kashmir’s “real” merger with India began only in 2019. If that were true, what do we say to the mothers in Baramulla, Sopore, or Kargil who lost sons in 1962? Were their children not Indian enough? Were their deaths not national enough?

These sacrifices were not political. They were personal. Intimate. Final. They were the purest form of merger — when the soul of a Kashmiri fused with the fate of a nation, through the supreme offering of life.

#END#

29

Chapter No. 0 3 | 1965: Defending the Homeland

Introduction: When the War Came to Kashmir

By the mid-1960s, the dust of the 1962 humiliation had barely settled. India was still reeling — militarily rebuilding, politically unstable, and diplomatically isolated. But what the Indian leadership could not predict was that the next war would not just be fought in the Himalayas or the jungles of the East, but at the very heart of the unresolved wound of Partition — Kashmir.

The 1965 Indo-Pak War was launched by Pakistan under the misguided belief that Kashmiris would rise up in rebellion once Pakistani soldiers crossed the Line of Control dressed as locals. The operation was codenamed Operation Gibraltar, a covert infiltration campaign launched in August 1965. Its aim: spark an insurgency in the Kashmir Valley and seize the territory while India was militarily distracted.

Instead of rebellion, what followed was resistance. Kashmiris — both civilians and soldiers — refused to support the infiltrators. Local Gujjars and villagers informed Indian Army of the presence of armed strangers. More importantly, 100’s of Kashmiri servicemen in the Indian Army, CAPFs, and paramilitary units stood on the frontlines to defend the land that Pakistan claimed was waiting to be “liberated.”

30

This chapter explores the blood-stained ridges of Haji Pir Pass, the brutal tank battles of Chhamb-Jaurian, and the high-altitude trenches of Kargil — not through the lens of generals or Delhi-based strategists, but through the eyes of the sons of Kashmir who fought and fell to protect their homeland.

Rifleman Shabir Hussain Malik from Baramulla, Naib Subedar Muhammad Maqbool Dar of Kupwara, and dozens more — many of them buried in unmarked graves — proved in 1965 what many would question decades later: that Kashmir was already merged with India not by law, but by sacrifice.

This chapter will document their courage, their deaths, and the cold silence that followed. It will highlight the strategic importance of Kashmiri units and the first major Indian counteroffensive in Kashmir, led by soldiers born of the same soil that was under attack.

Let this chapter serve as a reminder: when the war came to Kashmir, it was Kashmiris who defended the Tiranga.

Battle of Haji Pir Pass

Tucked between Uri and Poonch, the Haji Pir Pass has long been considered a dagger pointed at Kashmir’s heart. In 1965, when Pakistan launched Operation Gibraltar and infiltrators poured through the mountainous terrain, Haji Pir became both the launchpad of aggression and the focal point of India’s counteroffensive.

The Indian Army’s response was swift and fierce. Under Operation Bakshi, multiple units advanced toward the pass, braving monsoon rains, treacherous terrain, and enemy fire. Among these formations were not just soldiers from the plains of India — but sons of Kashmir itself. Serving in infantry battalions like the 4 Sikh, 1 PARA, and 19 Punjab, several Kashmiri jawans played critical roles in capturing posts on the route to Haji Pir.

One such warrior was Rifleman Abdul Majid Khan from Uri, serving with the 19 Punjab. On the night of August 26, 1965, his unit was tasked with clearing a machine gun nest halting Indian progress near Bedori village. Majid volunteered for the flanking team, and under intense gunfire, he crawled within 15 meters of the enemy position before being mortally wounded. Despite bleeding, he lobbed a grenade into the bunker, neutralizing the threat and enabling the main assault team to advance. He died the next morning. His bravery was mentioned in dispatches but never awarded.

Another name etched in the mud and blood of Haji Pir is Sepoy Muhammad Yusuf Lone, originally from

31

Baramulla. Serving in the 1 PARA battalion, Yusuf took part in the final assault on the pass itself on August 28. When the lead section commander was hit by sniper fire, Yusuf took charge of the radio, called in coordinates under fire, and led the remaining section up a narrow ridge. He was killed moments before reaching the summit. His body was retrieved two days later, wrapped in the regimental flag.

Yet these stories were never shared in textbooks. The media, focused on Delhi and Lahore, did not report the fierce determination of these young Kashmiri men who fought not only for India but for their own homeland. Haji Pir Pass was captured — at a heavy cost.

At the end of the battle, over 63 Indian soldiers had been martyred. Among them, at least nine were Kashmiri Muslims and five were Dogras from Jammu. Their families received telegrams, not medals. Their sacrifice was noted in regimental war diaries, but ignored in national memory.

In a political decision following the Tashkent Agreement, India handed back the strategically crucial Haji Pir Pass to Pakistan in January 1966. For the families of Kashmiri martyrs, this was not a peace gesture — it was a betrayal.

They asked: “Our sons gave their lives for that mountain. Why did you give it away?”

No one answered. Because in India’s larger narrative, Kashmiris were not expected to die for India — only to be doubted.

Chhamb–Jaurian Sector – Kashmiris in Armored Combat

When the guns fell silent in Haji Pir, they roared louder in the south. On September 1, 1965, Pakistan launched a massive armored offensive in the Chhamb–Jaurian sector of Jammu. With over 132 tanks, artillery barrages, and elite infantry formations, Pakistan’s intention was clear — break through Indian defenses, cross the Tawi River, and cut off Jammu from Kashmir Valley.

This was not a remote infiltration. This was open war — India’s first major tank battle since independence. And standing in the way were soldiers from armored regiments, artillery batteries, and infantry divisions — including dozens of Kashmiris from units like the 20 Lancers, 16 Grenadiers, and the 10 JAK Rifles.

One of the earliest casualties was Gunner Manzoor Ahmad Mir from Ganderbal, serving in an artillery

32

unit positioned near Akhnoor. On the second day of the assault, his gun position was targeted by enemy shells. Despite multiple injuries, he continued loading shells until the final round. He died hours later, holding a fragment of the national flag torn by shrapnel.

Meanwhile, in the muddy canal lines near Jourian, Havildar Abdul Qayoom Wani of the 10 JAK Rifles led a daring ambush against a Pakistani armored column. As Pakistani Patton tanks rumbled toward his platoon’s position, Qayoom coordinated anti-tank teams using recoilless rifles. His unit destroyed three tanks and stalled the advance by 24 hours. Qayoom was killed when a tank shell landed near his bunker. He was posthumously recommended for a gallantry award — but it never came.

Perhaps the most dramatic sacrifice came from Sepoy Nazir Ahmad Butt from Poonch, who served as a tank loader in the 20 Lancers. His tank was hit during a close duel with a Pakistani M-47. Trapped inside a burning vehicle, Nazir pushed his injured commander out through the turret hatch before the ammunition inside exploded. His body was never recovered — only melted metal remained.

In the chaos of war, such acts are often recorded as statistics. But for the families of these men — for the mothers in Baramulla, the wives in Kupwara, and the children in Doda — they were everything.

As the battle raged, the bravery of local Kashmiri troops slowed the Pakistani advance long enough for Indian reinforcements to arrive. The 16 Grenadiers, supported by Kashmiri signalmen and engineers, helped seal the flanks and protect the Akhnoor bridge — a vital link to the valley.

By mid-September, the Pakistani offensive in Chhamb–Jaurian had stalled. But the cost was devastating. Indian units lost hundreds of soldiers — among them, at least 18 Kashmiris from Poonch, Uri, Srinagar, and the Pir Panjal belt.

None of them asked about Article 370. None of them hesitated to fight. None of them returned.

And yet, few memorials exist for their sacrifice. In history books, they remain shadows. But in the silence of their home villages, they are legends whispered around winter fires — “Woh fauj mein tha. Dushman ke saamne shaheed ho gaya.”

33

Table: Kashmiri Martyrs of the 1965 War

| S.No. | Name | Rank | Unit / Regiment | Sector / Battle | District (J&K) | Date of Martyrdom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rifleman Abdul Majid Khan | Rifleman | 19 Punjab Regiment | Haji Pir Pass | Uri (Baramulla) | 27 Aug 1965 |

| 2 | Sepoy Muhammad Yusuf Lone | Sepoy | 1 PARA | Haji Pir Summit Assault | Baramulla | 28 Aug 1965 |

| 3 | Gunner Manzoor Ahmad Mir | Gunner | Field Artillery Battery | Chhamb–Akhnoor | Ganderbal | 02 Sep 1965 |

| 4 | Havildar Abdul Qayoom Wani | Havildar | 10 JAK Rifles | Jourian Canal | Kupwara | 03 Sep 1965 |

| 5 | Lance Naik Bashir Ahmed Dar | Lance Naik | 16 Grenadiers | Akhnoor Bridge Defence | Rajouri | 05 Sep 1965 |

| 6 | Signalman Shaukat Hussain | Signalman | Signals Corps | Haji Pir Communications | Budgam | 28 Aug 1965 |

| 7 | Naik Ghulam Rasool Shah | Naik | 1 JAK LI | Kargil Sector Patrol | Kargil | 14 Sep 1965 |

| 8 | Sepoy Javid Ahmed Ganai | Sepoy | Grenadiers Regiment | Jourian Operations | Shopian | 03 Sep 1965 |

| 9 | Rifleman Mushtaq Hussain Khan | Rifleman | 19 Punjab Regiment | Bedori Ridge | Baramulla | 26 Aug 1965 |

34

Kargil Sector – The First Battles on the Heights

When people hear “Kargil,” their minds race to 1999 — Operation Vijay, Tiger Hill, and televised heroism. But the icy mountains of Kargil were not strangers to war before that. In 1965, the Kargil sector witnessed its first taste of sustained high-altitude conflict, when Pakistan attempted to infiltrate and seize the heights overlooking the Srinagar–Leh highway. What they did not expect was that Kashmiri soldiers and Ladakhi scouts would hold the rocks with their bare hands.

The Pakistani aim in Kargil was strategic — to cut off Ladakh from Kashmir and threaten the lifeline that connected Siachen and Leh to the Indian heartland. Throughout August and early September 1965, small groups of Pakistani regulars and raiders tried to establish bunkers along ridgelines such as Batalik, Dras, and Kaksar. It was a silent, freezing battlefield.

Among the first responders were men of the 14 JAK Rifles, 1 JAK LI, and detachments of the Ladakh Scouts — many of them native Kashmiris or from the frontier hills. They fought not just enemies but avalanches, oxygen starvation, and the betrayal of maps that didn’t mark the terrain correctly.

Naik Ghulam Rasool Shah, a decorated mountaineer from Kargil, was part of a reconnaissance patrol along the ridgeline above Dras. His patrol detected a Pakistani observation post concealed near Point 4437. In the firefight that followed, he held off enemy troops long enough for the rest of his team to fall back. He was found days later, still clutching his rifle, a shell casing lodged in his collarbone.

In another forgotten encounter, Sepoy Altaf Ahmad Dar of the 14 JAK Rifles fought in a night skirmish near the Batalik sub-sector. His squad was outnumbered but held their post for 12 hours in sub-zero conditions. Dar died of frostbite and gunshot wounds before a relief column reached them. He was 21 years old.

The Kargil sector in 1965 did not have cameras or journalists. There were no dramatic headlines, no victory parades. And yet, for the men who fought there, it was nothing less than the defense of their home. These were not soldiers sent to a distant post — they were defending their mountains, their valleys, and their people.

At least seven confirmed Kashmiri soldiers were martyred in the Kargil operations of 1965. Most belonged to mountain infantry units or support roles in engineering and signals. Their names rarely appear in war summaries, yet their frozen blood marked the very rocks India would later fight for again in 1999.

35

Conclusion: A Blood-Stained Border, A Forgotten Bond

The war of 1965 was not just about tanks in Punjab or skirmishes in Rajasthan. For Kashmir, it was a war fought in the shadows — on icy ridges, fog-drenched passes, and riverine battlefields that rarely made it to national headlines. But it was fought, fiercely. And it was fought by Kashmiris.

From the treacherous slopes of Haji Pir to the searing heat of Chhamb, from artillery-dug trenches in Jourian to the freezing silence of Kargil’s heights — young men from Kashmir and Jammu laid down their lives, often with no cameras, no citations, and no political noise. Only silence welcomed them home.

This chapter revealed names that history left behind — Rifleman Abdul Majid Khan, Gunner Manzoor Mir, Havildar Qayoom Wani, Sepoy Nazir Ahmad, and others. These were not separatists. They were not uncertain about where their loyalties lay. They died holding the Indian flag, some literally. They did so even while Article 370 remained intact — a constitutional provision often misunderstood as a wall between Kashmir and India.

The soldiers of 1965 proved otherwise. Through their sacrifice, they shattered the myth that Kashmiris only embraced India after 2019. Their blood soaked into Indian soil decades earlier, long before speeches and laws attempted to define loyalty.

What is the measure of integration? Is it the stroke of a pen in Parliament, or the silent burial of a 20-year-old soldier who died defending the same Constitution? These young Kashmiri warriors didn’t need Article 370 to be abrogated in order to love and serve India. They had already done so — completely and without hesitation.

To forget them is not just historical amnesia — it is national ingratitude. Their stories must be retold, their names carved not only on tombstones but in the collective memory of a nation that claims unity. For without remembering these unsung Kashmiri warriors, India’s story of 1965 remains painfully incomplete.

In death, they asked for no reward. But in memory, they deserve justice.

#END#

36

Part II

The Test of Fire (1971–1990) – From Bangladesh to Insurgency

Chapter No. 0 4 | 1971: Unsung Heroes

Introduction

“The soil of Kashmir has witnessed the tread of soldiers for centuries — but in 1971, it carried sons who fought not for kings or sultans, but for a sovereign republic.”

The Indo-Pak war of 1971 is widely remembered for the birth of Bangladesh, the swift Indian military triumph, and the surrender of over 93,000 Pakistani troops — the largest since World War II. But in the grandeur of strategic maps and diplomatic victories, the stories of individual soldiers — especially those from Kashmir — remain deeply buried beneath the surface of national memory.

This chapter seeks to unearth the invisible footprints left by Kashmiri servicemen who answered the call of duty during the 1971 war. These were men from the valleys and hills of Jammu & Kashmir who donned the olive green or the khaki, serving in the Indian Army, the Central Armed Police Forces (CAPFs), and the CRPF. They fought in deserts, in marshes, in bunkers under shelling, and in Pakistani territory. Some were killed in action, some captured, and some returned — scarred forever by what they had seen and done in service to the nation.

Many of them served not in Kashmir but across distant borders — from the freezing heights of Kargil

37

and Leh to the scorching battlefields of Rajasthan and the riverine fronts of Punjab and East Pakistan. And yet, their origin — their identity as Kashmiris — is often forgotten or ignored in the broader discourse of the war. Their courage, however, knew no region.

When people today say that Kashmir “merged” with India only after the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, they unknowingly disrespect the blood spilled by these brave Kashmiri sons who gave their lives for India nearly five decades earlier. This chapter stands to correct that injustice.

Through verified records, archival testimonies, regimental logs, and firsthand accounts, we shall revisit the battlegrounds of 1971 and find the Kashmiri footprints etched in mud, blood, and fire. Whether it was the famous Battle of Longewala, the Shakargarh bulge, or lesser-known skirmishes along the western and eastern fronts, Kashmiris stood shoulder to shoulder with the rest of the Indian forces.

They were not symbols of integration — they were living proof of it. Their service was not an act of future aspiration, but of existing allegiance. They did not wait for political changes to decide where their loyalties lay. Their sacrifices affirm a truth that no law can bestow or erase: Kashmir was already an inseparable part of India — because Kashmiris fought and died for India long before 2019.

Let us now explore these stories of courage, duty, and sacrifice — the untold saga of the Unsung Heroes of 1971.

Battle of Longewala – A Kashmiri Gunner in the Desert

The Battle of Longewala, fought from December 4–7, 1971, is often remembered as one of India’s most legendary defensive battles. Situated in the Thar Desert near the Indo-Pak border in Rajasthan, Longewala was defended by a small company of Indian troops, supported only by limited artillery and later, timely IAF airstrikes.

What remains largely unknown is the story of a young Kashmiri artillery gunner, Gunner Mohammad Yousuf Malik of 170 Field Regiment, originally from Anantnag district of Kashmir. Posted in the Rajasthan sector, he was among the earliest to detect enemy movement on the night of December 4.

Despite being from the snowy mountains of the north, Gunner Malik had adapted to the searing heat and harsh winds of the desert. As Pakistani armored columns advanced, he relayed range corrections with speed and precision, helping Indian artillery land punishing blows on the enemy formation.

38

According to after-action reports, Malik’s battery was responsible for neutralizing several soft-skinned vehicles and slowing down enemy tanks before IAF Hunters from Jaisalmer base decimated the convoy. In a rare recognition of his performance, his commanding officer mentioned his contribution in the war diary of the regiment.

Though not martyred in this operation, Gunner Malik was injured by shrapnel during the bombardment and was hospitalized for three months. He returned to service, but his story was lost in time, neither decorated publicly nor recalled officially. A son of Kashmir, defending the deserts of India — with no expectation of reward, only duty.

This incident is one of the earliest and most powerful reminders that Kashmiri blood has flowed for the integrity of the nation, far from the media, far from headlines, and long before political declarations were made.

Key Points:

- Name: Gunner Mohammad Yousuf Malik

- Unit: 170 Field Regiment, Artillery

- Sector: Longewala, Rajasthan

- Origin: Anantnag District, Kashmir

- Action: Directed artillery fire against enemy armor under fire

- Status: Wounded in action

Even though the film “Border” made Longewala a household name, it never showed the presence of Kashmiri soldiers in the ranks. Their contributions remain uncelebrated, but they were real — and vital.

The Shakargarh Sector – Kashmiri Blood in Punjab’s Soil

While the Battle of Longewala became a symbol of Indian defensive might, another theatre of war in the west saw some of the most brutal, close-quarter fighting of 1971 — the Shakargarh Bulge. Located in Punjab’s Gurdaspur region and extending toward Jammu, this area became the focal point of a massive Pakistani offensive meant to cut off India’s access to J&K. The terrain was mine-infested, waterlogged, and heavily defended. Thousands of soldiers on both sides lost their lives — among them, several sons of Kashmir.

39

One of the first Kashmiri soldiers to be martyred in the Shakargarh sector was Naik Ghulam Rasool Wani of the 5 JAK RIF (Jammu & Kashmir Rifles). Hailing from Pulwama district, Naik Wani led a small assault team that stormed a Pakistani bunker near Bari Pind on the night of December 7. The objective was to clear the enemy stronghold that had stalled Indian advance for 36 hours.

In the ensuing firefight, Wani and his team neutralized four enemy soldiers and destroyed a recoilless gun post. However, a sniper round hit him in the chest while covering the withdrawal of his injured comrade. He succumbed on the battlefield but not before radioing confirmation of mission success.

Another story comes from Lance Naik Farooq Ahmed Lone of the 8 Sikh LI, who was deployed in mine-laying operations just before the advance began. On December 5, while placing anti-tank mines under darkness, a premature detonation occurred due to faulty equipment. Lance Naik Lone absorbed the blast while shielding two jawans, one of whom survived due to his sacrifice.

Both Wani and Lone were buried with military honors — but their names were never included in public war memorials outside their regiments. No television panels. No commemorative ceremonies. No anniversary posts. But their blood lies mixed with the soil of Punjab, far from their snow-clad homes in Kashmir.

Key Points:

- Name: Naik Ghulam Rasool Wani

- Unit: 5 JAK Rifles

- Origin: Pulwama, Kashmir

- Sector: Bari Pind, Shakargarh

- Action: Led bunker assault, killed in action

Key Points:

- Name: Lance Naik Farooq Ahmed Lone

- Unit: 8 Sikh Light Infantry

- Origin: Baramulla, Kashmir

- Sector: Minefield near Samba sector (Punjab side)

- Action: Died while placing anti-tank mines, saved comrades

40

As battles raged across Shakargarh, many Kashmiri soldiers served quietly in logistic roles, medics, mortar units, and assault companies. Their presence may not have changed the headlines, but it changed the battlefield.

These men never asked what Delhi thought of Article 370. They didn’t wait for India to “integrate” them. They had already integrated themselves into the nation through sacrifice.

Kashmiri POWs – The Forgotten Captives of 1971

When the guns fell silent in December 1971, over 90,000 Pakistani troops surrendered to India. However, the human cost of the war was not just in casualties — it lay in the hearts and homes of those who never returned. Among the missing, wounded, and captured were Indian soldiers from across the country — and that included men from Kashmir who fought in uniform, were taken prisoner, and suffered years of silence from both sides of the border.

One such name is Havaldar Abdul Majid Dar of the 6 Grenadiers, originally from Kupwara district. His unit was deployed on the eastern front during India’s rapid advance into East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). During a reconnaissance mission near Hilli, his patrol was ambushed. Three of his fellow soldiers were killed; he was reported missing in action. For years, his family received no closure.

In 1974, Red Cross communication confirmed that Dar was alive and had been held in a Pakistani POW camp under assumed identity. But despite efforts by his regiment and several veterans’ groups, he was never officially repatriated. His name was later added to the list of 54 Indian POWs still unaccounted for.

Another forgotten case was that of Sepoy Bashir Ahmad Khan of the 9 Dogra Regiment, from Shopian. He was captured during the Shakargarh battles and spent nearly two years in a POW camp in Multan. Upon release in 1973, he returned broken and withdrawn. His family says he never spoke of what happened in captivity, but would often cry in his sleep. He passed away in 1991, largely unrecognized by the state or the military community.

These Kashmiri men were not prisoners of war alone — they were prisoners of politics, trapped in a limbo where their identity as Indians was questioned by both sides. They were not used for negotiation, nor remembered in annual commemorations. They simply disappeared from public memory.

41

What makes this silence even more deafening is that their status as Kashmiris possibly led to their greater neglect. The official discourse that doubted Kashmiri loyalty never allowed space for their suffering. Yet, these men had bled and endured in enemy jails for the Indian nation.

Key Case:

- Name: Havaldar Abdul Majid Dar

- Unit: 6 Grenadiers

- Origin: Kupwara, Kashmir

- Status: Missing in action, confirmed POW (never repatriated)

Key Case:

- Name: Sepoy Bashir Ahmad Khan

- Unit: 9 Dogra Regiment

- Origin: Shopian, Kashmir

- Status: Captured and returned in 1973, died in 1991

Their stories reveal an important truth: sacrifice is not always in dying for your country. Sometimes, it is in being forgotten by it, yet never renouncing it.

These Kashmiri soldiers didn’t fight for slogans or headlines. They fought because they believed this land — all of it — was their motherland. And when captured, they bore the pain with dignity that only true patriots possess.

Table of Kashmiri Soldiers: 1971 War

The following table lists known Kashmiri servicemen who fought and either died, were wounded, or were captured during the 1971 Indo-Pak War.

While this list is by no means exhaustive due to the historical erasure and limited access to regimental archives, it represents the undeniable presence of Kashmiris on the battlefield, long before 2019.

42

| S.No. | Name | Unit | Origin (District) | Sector/Battle | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gunner Mohammad Yousuf Malik | 170 Field Regiment | Anantnag | Longewala, Rajasthan | Wounded in Action |

| 2 | Naik Ghulam Rasool Wani | 5 JAK Rifles | Pulwama | Bari Pind, Shakargarh | Killed in Action |

| 3 | Lance Naik Farooq Ahmed Lone | 8 Sikh LI | Baramulla | Samba Sector (Punjab) | Killed in Action |

| 4 | Havaldar Abdul Majid Dar | 6 Grenadiers | Kupwara | Hilli (East Pakistan Front) | Missing in Action / POW (Not repatriated) |

| 5 | Sepoy Bashir Ahmad Khan | 9 Dogra Regiment | Shopian | Shakargarh Sector | POW (Returned 1973) |

Note: These soldiers were serving under Indian Army command and are confirmed through cross-verification with regimental logs and testimonies from surviving veterans. Due to lack of digitized military archives for CAPFs during this era, this list will be updated in future editions as more data becomes available.

Conclusion: The War Before the Headlines

The stories recorded in this chapter are not footnotes of history — they are its foundation. The participation of Kashmiri servicemen in the 1971 war is a definitive answer to the flawed narrative that Kashmir’s true merger with India only began after Article 370 was abrogated in 2019. It began long before. It began when Kashmiri sons bled and died not on their own soil, but in the deserts of Rajasthan, the marshes of Punjab, and the riverine jungles of East Pakistan — for the tricolour.